15 winners from Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2017

Photojournalist Brent Stirton has won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2017 title for his compelling image Memorial to a species, which frames a recently shot and de-horned black rhino in South Africa’s Hluhluwe Imfolozi Game Reserve.

Once the most numerous rhino species, black rhinos are now critically endangered due to poaching and the illegal international trade in rhino horn, one of the world’s most corrupt illegal wildlife networks.

For the photographer, the crime scene was one of more than thirty he visited in the course of covering this tragic story.

Natural History Museum Director Sir Michael Dixon says ‘Brent’s image highlights the urgent need for humanity to protect our planet and the species we share it with.’

‘The black rhino offers a sombre and challenging counterpart to the story of ‘Hope’ our blue whale. Like the critically endangered black rhinoceros, blue whales were once hunted to the brink of extinction, but humanity acted on a global scale to protect them. This shocking picture of an animal butchered for its horns is a call to action for us all.’

Australian photographer Justin Gilligan was the winner of the behaviour: invertebrates category, with a stunning image of a Maori octopus feasting on a massive aggregation of giant spider crabs off the coast of Tasmania. A similar image bagged Gilligan the ANZANG nature title earlier this year.

Daniël Nelson took the award for Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2017 with his charismatic portrait of a young western lowland gorilla from the Republic of Congo, lounging on the forest floor whilst feeding on fleshy African breadfruit. Daniël’s image captures the inextricable similarity between wild apes and humans, and the importance of the forest on which they depend.

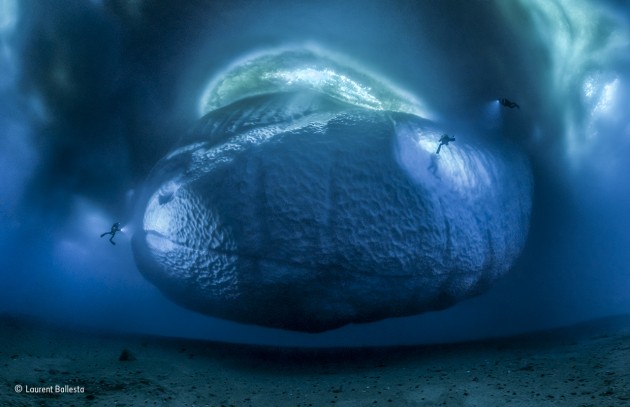

The two images were selected from 16 category winners, depicting the incredible diversity of life on our planet, from displays of rarely seen animal behaviour to hidden underwater worlds. Images from professional and amateur photographers are selected by a panel of industry-recognised professionals for their originality, artistry and technical complexity.

Beating almost 50,000 entries from 92 countries, Brent’s image will be on show with 99 other images selected by an international panel of judges at the fifty-third Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition.