The challenge of shooting successful environmental portraits is revealing the whole story in just one frame. It's not easy and even the best shooters struggle at times to do it well. In an effort to demystify this challenging area of photography, Rob Ditessa talks to three top pros – Nick Bassett, Matt Devlin and James Braund – to get their best tips for shooting powerful in situ portraits.

For Sydney-based photographer Nick Bassett, the challenge of environmental portraiture isn't always just the photo.

"I photographed a teapot collector for a series on different types of collectors recently. I was working in a tiny teahouse in the Blue Mountains, using two big studio lights on stands, a tripod and an assistant. The hardest thing wasn't even the photos, but that either of us could have knocked over a studio light and smashed some of the fragile collection of valuable antique porcelain teapots! We also had the added pressure of a coach-load of tourists streaming into the already jam-packed teahouse before we'd even packed up."

"Janet Williams is now retired," says Nick Bassett. "At the time Janet was also on the tourist trail with her vast collection of over 10,000 pieces of royalty memorabilia, in Woonona New South Wales which is near Wollongong." Canon 1DS Mark II, 24-70mm f/2.8 @ 25mm, 1/40s @ f/4.5, ISO 200.

BUILDING A RAPPORT

Compared to more traditional studio style portraits, an environmental portrait is the difference between taking a photograph at a location, and taking a photograph because of the location, where the background is as much a subject as the person.

"While some people feel comfortable in their familiar environment and become distracted from the photography, others feel vulnerable, as much as in a studio," says Bassett. "The tricky part is dealing with people who are essentially uncomfortable with being photographed."

For Bassett, building a rapport quickly is critical to overcome this. His genuine interest in people helps break down barriers quickly, but he stresses that because every element in an image plays a part in telling the overall story, he pays close attention to expressions, body language and attire. During the shoot he explains how he is going to work, sets the scene, and provides feedback and positive reinforcement.

"As we go along, I'm shooting very fast to create and capture the moment when the guard has dropped and their true personality and expression comes through. I find the winning shot expression emerges in the split second when the subject briefly forgets that they are being photographed."

"Having said that, I often don't have the time or the capacity to dress and style my subjects, and so sometimes you just have to work with what you're given. I was lucky in the example of the collectors' images because each of those subjects was well prepared and had a very strong and unique sense of style that followed through to what they wear."

For Perth freelance photographer Matt Devlin, his own research and chatting with his subjects is the first step to taking successful portraits.

"As soon as you ask someone to talk about something they are passionate about, they're off to the races," he says. "I use it to bond with the people at the time, and when they're finished telling me, they are a lot more relaxed."

The composition of this shot by Matt Devin is driven by the leading lines and the flare which adds depth through the frame. Fujifilm X100S, 1/500s @ f/4, ISO 640.

Melbourne portrait and reportage photographer James Braund agrees. With easy access to information on the Internet, there is no excuse for being unaware of background information about a subject before meeting them. Many of his clients will offer more specific direction, but some, such as one long-standing customer, will send him a three-line email identifying the subject and objective of the shoot.

Beforehand Braund develops an idea about how to approach the shoot, but whether or not this happens on the day is another thing. On the shoot, he shakes hands, looks the subject in the eye and outlines his intentions, asking if they are agreeable. Usually, he then talks about anything but work, and is always "on", engaged with the subject, being respectful, speaking clearly and listening, and doing his best to make the shoot as painless as possible for the subject.

"I'll get them to show me how they work, and while they're doing it, I'll be watching for that iconic moment that captures them, that people will recognise themselves in, and say, 'It feels right'. I'm looking for what will look right while they're naturally doing that activity, and then I try to shape it."

James Braund took this portrait of squash champion Reyna Pacheco at a squash court in Kooyong, Victoria, for Getty Global Assignments. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, EF50mm f/1.2L lens @ 50mm, 1/160s @ f/4.5, ISO 200.

COMPOSITION IS KING

Matt Devlin spends considerable time on composition – although this is sometimes as much a challenge as relating to his subject. Devlin is a firm believer that the personality of the subject and the type of location are the elements that drive composition.

"If you turn up to take a photo of a farmer in a grain shed, the grain shed is what it is. You have to work with the location, and then the other part of image making is how it feels. You have to portray the tone or feeling of the activity. You would never use 'beauty' lighting or look for composition that had a lot of grace and flow for, say, a farmer or a mechanic.

"As a rule, don't have people facing directly at the camera, the arms dropped by their side, dead square. If you can, turn someone to 45 degrees and get them to put one hand in their pocket: they look instantly relaxed. Nobody stands and talks to somebody directly face on. It's little things like that, you have to watch for. You've got to get people to move in the photo, the way they move in life," suggests Devlin.

For James Braund, it's more about feeling. While shooting, he explains, his mind is assessing every aspect within frame, because he doesn't want to have to think about aperture or, for example, if the second head is firing. He wants to be totally present with the subject and ready to react to whatever minor nuance they display.

"Every shoot is different, so depending on the subject and client, I'll assess backgrounds, lighting level, physical space, and the amount of variations I could achieve," says Braund. "Then I'll consider the technical aspects such as lighting options, camera angle, distracting elements, and height and body shape. If time permits, I'll make wardrobe suggestions, and also what not to wear."

Nick Bassett says his style and technique changes depending on his subject.

"One of my favourite styles is to shoot macro images in a small space. It is a technique that I love and have spent a long time fine-tuning because it allows me to portray something in a completely new light. But all my images are always rich in colour, contrast, and graphic composition.

"Much like the Impressionists used a very pastel-coloured palette reflecting their European surroundings, I want my work to reflect Australian light which is very bright, colourful, and high in contrast. On top of this I tend to bring a strong design sensibility to my photography, an influence that I get from my dad who was a graphic designer."

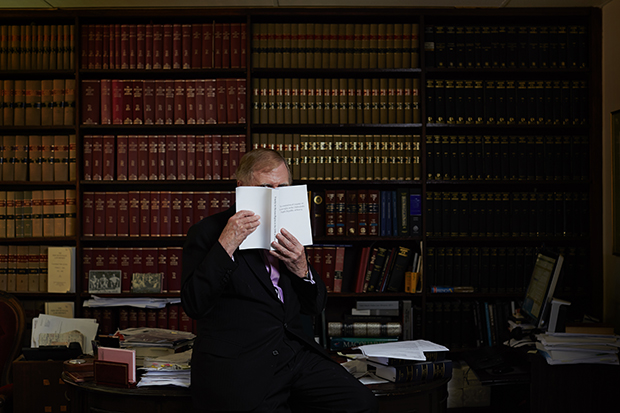

James Braund took this photo of Michael Kirby in his Chambers in Sydney for a personal project. "This is an out-take of one of the more serious portraits. I first met Michael when covering the International Aids Conference in 2014 for the International Aids Society. It was a difficult time for people with the MH17 disaster recently claiming many lives, including many staff and personnel who were en route." he says. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 50mm f/1.2L lens @ 50mm, 1/40s @ f/3.5, ISO 160.

GETTING TECHNICAL

"The most important piece of equipment is between your ears," says Braund. Although he uses a Canon EOS 5D Mark III, he's no gear head. The silent feature on the Mark III, he says, is fabulous, and although he sees big advantages with mirrorless systems, he's not willing to change just yet. Attached to his camera bodies he has Canon L Series lenses, 35mm f/1.4, 50mm f/1.2, and 85mm f/1.2. His zooms include a 17-40mm f/4, 70-200mm f/2.8 and an old 24-70mm. The zooms however, tend to stay on the shelf.

"I believe there is a lot to be said for using one focal length," says Braund. "This maintains perspective and forces the photographer to notice aspects within the frame. It's also a great discipline. If you want to zoom in, go forth. You want to zoom out? Walk backwards. I'm not a fan of super wide and long lenses, but they certainly have their applications."

"This was a three-light setup, two on the subject, and one bounced off a wall, says Matt Devlin. "For fill, I used natural light from the shed door on the truck, then used light and lines to create a flow through the frame. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 1/100s @ f/6.3, ISO 3200.

With constant upgrades and rapidly changing technology, he now prefers to hire equipment. After experiencing problems with the recycling speed of flash equipment, output power, and communication between transmitter and receivers with certain gear in the past, he pays for the best equipment to reduce the chances of this happening. There are many links in a chain for a system to operate at peak efficiency, and location photography is no different.

Should you ever use on-camera flash in taking a portrait? There is nothing wrong with direct flash but it all depends on the effect you are after advises Braund. He recommends using off-camera flash and experimenting to attain more flattering results. Tripods he finds frustrating and slow, but on certain commissions he needs one. He believes Sony's image stabilised bodies and various lens technologies have made tripods less important in certain situations.

In remotes, he has the Profoto Air system and pocket wizards because they never miss a beat. Remotes, he says, are convenient if lights are inaccessible. It saves pulling the stand down, and adjusting it, and certainly speeds up the shoot. UV filters are the only filters for which he sees any need.

Although he has not used a light meter for some time, just recently he found the need for one when he became frustrated that he could not see the histogram on the rear LCD. He now has one in his kit again. They are faster to work with instead of wasting time with LCD screens. Included in his go-to kit are small and large soft boxes with egg-shell grids, grid spots, and standard reflectors, "to just add to whatever light as a slight fill".

His favourite item in the kit is a "hyper juice battery" from which he can run a laptop to work on for a few hours when he is in transit. It also has two USB ports for phone charging. His 4G Pocket Wi-Fi has saved him a few times.

Devlin's kit includes three cameras, a Fuji X100, a Canon 5D Mark II, and a Canon 1D Mark IV with Canon lenses, 17-40mm, 24-70mm, 24-105mm, and 70-200mm, an Elinchrom Quadra lighting set-up in their two light kit, three Speedlights, some wireless transceivers, and a handful of mixed gels. On top of that he has soft boxes, stands, sweepers, and other equipment, "but for the nuts and bolts of getting it done, that's it", he says.

While he owns a tripod, Devlin rarely uses it. "I find the way I shoot is very fluid. People move in these environments. There's a lot of moving backwards and forwards, and you're constantly refocusing. I find the tripod photos come out too stiff but then there are times when you want a certain background movement to happen where you have to use the tripod, and I just have to get around it."

His boot contains sandbags, to keep the stands steady in windy conditions, and he suggests keeping some safety pins at the ready, to pinch in clothes or hold something in the background. His kit does not include a light meter because part of his style in chatting with the subject is to show them the effects of different lighting and views. "People can see the improvements and that you're not mucking around. I think that opens them up a lot too. I just use the back of the camera and chimp away," Devlin says.

Deliberating on advice for someone trying their hand in this genre, he sums up, "As far as the technical information, I would ordinarily try and shoot environmental portraits like my shot of the teapot collector using a wide angle lens, 24mm or wider. When shooting with such a wide lens, this gives you the capability of shooting at a wider aperture and still getting everything in focus because there is very little distance in this kind of small-room environment from one side to the other.

"Depth of field depends on the shot but with environmental portraiture you generally want to use an aperture of f/11-22 so that the background is also in focus. An environmental portrait needs context for it to work; it is important that the background or the foreground, or both, are clear in the image."

Having used an array of different cameras in film and digital, medium-format and 35mm, Nick Bassett is not one to get caught up on gear. It's just a medium for capturing the image, but he has a few favourites that suit his work. His 'go-to' lenses are Canon 16-35mm f/4 wide angle, and 100mm f/2.8 macro. The 100mm macro lens is versatile because you can use it for extreme close-ups as well as portraits and landscapes and it is comfortable to carry for long periods of time.

Bassett is a big fan of using studio lighting on location so he can have control over the lighting regardless of the available light. Battery-powered and triggered wirelessly, studio lights are easy to use.

"Claudia Chan Shaw is a fashion designer, among an array of other talents, and is involved in various ventures," says Nick Bassett. "Years after I took this shot Claudia went on to co-host the ABC show Collectors from which my initial inspiration to do the series came." Nikon D200, 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 @ 27mm, 0.3sec @ f/8, ISO 200.

LIGHTING ADVICE

Devlin believes the main technical challenge of environmental portraits is managing mixed lighting sources.

"Getting all the lights to blend together and look right, for example a lamp on a desk with a warm light, and a window light coming in from behind, all while you're trying to add a flash, can be a real challenge."

Among Devlin's solutions to common lighting problems are gels and 5-in-1 reflectors. "The value of those 5-in-1 reflectors for this work is immense. If you've got windows with direct light streaming through, you can put one up, even if it's outside over the window, to diffuse the light. If you need to bounce a bit of fill back, they're a big help. They give you options."

"Sometimes there may be a detail or an item in the background people do not want seen, but it's fine as texture in the image. Use a shallower depth-of-field to actually throw off some of the background to keep that private. It is just part of figuring out the composition," he says.

Starting out in this genre, a camera with low-light capability is important, though the lenses, Devlin suggests, can take a back seat as most of the work can be done at between f/5.6 and f/8, and even the nifty 50s, are surprisingly good at that sort of f-stop. "If you've got one light, and a 5-in-I reflector, and a camera with a lens, that's enough," he suggests.

A great starting point for beginners, he says, would be a couple of low-cost LED panel lights on stands. "Invest in a flash that can be mounted on a stand and trigger it remotely so you can position it away from the camera. Then as you get more serious, add more flashes to your lighting kit," he says. Bassett advises only ever using on-camera flash to bounce off the wall or ceiling.

For Bassett, tripods are vital. Many environments have very limited available light. Using a tripod allows him to get out from behind the camera to create and sustain rapport with his subject easily. Light meters are not critical as they once were, especially for beginners. A reflector is a very handy and cost-effective tool but the down side is you need an assistant to hold it. However, he suggests, even a basic kit should include a reflector and at least one flash. Bassett cautions, "Don't forget to continually meter for the shot. If you're shooting in manual you can get carried away and forget to keep checking your light meter as you go."

"This was taken with a two-light setup," says Matt Devlin. "I bounced light off the wall and ceiling of the entry at the back to provide a bright colourful background and a kicker to mimic and amplify the available light."

WORKFLOW AND POST

Turning to workflow and post-production, Devlin says his work "is basically done in camera". In Lightroom, he may make minor changes in contrast, and highlights to lower the glare. He uses Photo Mechanic to import everything initially to dual drives, one is a working drive and the other a backup. Because he snaps many test shots as he walks and talks, there are many images he doesn't need to keep. These he weeds out right away and imports his selection into Lightroom. After another cull, he may use Photoshop to touch up trickier problems but he does not use the program very much.

Bassett says he primarily uses Lightroom and Photoshop, "but post-production would comprise no more than 10 per cent of the process for me. I love the shooting part and would rather spend five more hours shooting to avoid spending one hour on the computer."

Braund explains his referred program is Capture One Pro and that he does most of his editing through it, lamenting that the, "excellent editing software called Media Pro is sadly no longer supported".

For high volume jobs, he uses Media Pro to ingest and annotate, and then transfers to C1 for processing. He will use Photoshop if any retouching is required.

For all three photographers, a common theme emerges. Taking successful environmental portraits is about nailing the basic skills of working with people and light – do that, and your story will reveal itself.

Article first published in Australian Photography (April, 2016).

James Braund's image of The Big Issue vendor, Phil. This portrait was taken at The Big Issue office in Melbourne. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF50mm f/1.2L USM, @ 50mm, 1/125s @ f/3.2, ISO 400.