Profile: Julio Muñoz, Cuba's cowboy photographer

The self-described John Wayne of Cuban street photography, Julio Muñoz, is a treasure trove of useful tips and tricks. AP editor Mike O'Connor spent two days learning from this modern-day master on a tour of historic Trinidad.

Spend enough time talking with people in Cuba, and there’s a Spanish expression you will probably hear: No es fácil — it’s not easy.

It’s an expression born of a special type of patience and stoicism. You might hear it in the queue to change money at the bank before you wait even longer still to buy a loaf of bread. It may be uttered by a self-taught mechanic tenderly turning a wrench on a 60-year-old car before it splutters back to life. You could probably hear it sighed collectively by the entire neighbourhood when the power goes out. For some Cubans, it comes from wanting to visit family in Miami, but never being able to afford the airfare. No es fácil seems to sum up this beautiful country perfectly.

It’s also an expression that Cuban horse-whisperer, former electrical engineer, cowboy and renowned photographer Julio Muñoz uses frequently to describe his life.

“I knew that photography was something I was interested in, but getting hold of a camera in Cuba is not easy,” he explains. Like many Cubans growing up after the 1959 revolution, Julio was forced to reinvent himself every time the economy changed, with photography just one of his many talents.

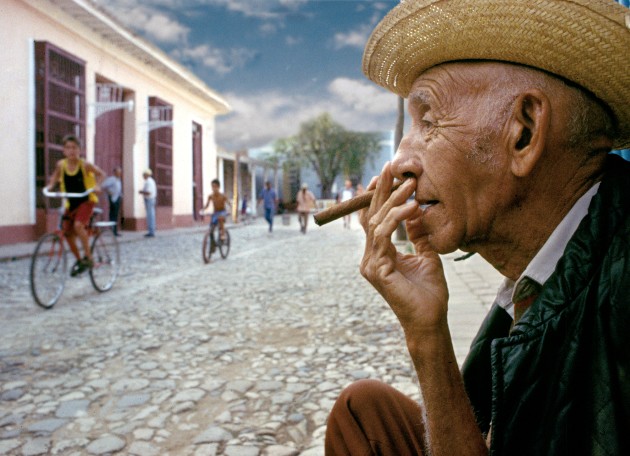

Julio's hometown of Trinidad is perhaps Cuba’s most recognizable city after Havana and a place of just 70,000 residents where rural and urban harmonise effortlessly. Horse drawn carts share the road with cyclists, while old 1950s cars idle next to buildings draped in beautiful pastel colours. Throw in a sun that casts a warm light across the north and south facing streets, equal parts catholic and African culture, and open, friendly people, and you’ve got yourself a stunning photographer’s paradise.

I’m staying with Julio in the family home he was born and raised in. Sitting proudly on a corner near the centre of the UNESCO world heritage city, it's a beautifully grand Spanish colonial house with peeling paint on the outside and original tiles on the inside. It also dates back to 1800 and has been in the Muñoz family for at least 130 years. Julio’s photos on the walls nestle next to images of his beloved horses and formal pictures of his children.

While doing research for my three-week trip to Cuba I had stumbled upon Julio’s striking and uncluttered street photographs of his hometown. Keen to get some tips to improve my own travel photos, I signed up on one of his hugely popular photo tours. But before any of that can happen, I’ve got some learning to do.

Starting out

“Traditional teaching of photography is really depressing,” says Julio, looking exasperated. “Think about the manual for a camera, it’s boring. Nobody wants to read that. My tips are simple – understand how to use the camera and have a clear sense about what it is you want to photograph – that's all.”

For Julio, there’s no need to fire away on the shutter, spraying photos everywhere. “My fourteen year old daughter can do that – life’s too short to take hundreds of photos. It’s about being ready to capture the decisive moment. One photo should be all you need.”

To me, it already sounds like a breath of fresh air in the world of technical jargon I’m exposed to everyday – but surely it can’t be that easy.

Before we set out Julio shares his preferred camera settings with me for shooting on the street, encouraging me to set my camera on shutter priority, with a low enough ISO to guarantee quality and still allow a fast enough shutter speed to freeze any action. “Real life is not blurry. Your images must be sharp or they are worthless,” he explains. “Check that you're getting an aperture which provides a generous depth of field, around f/8. If you can't get this, that's when you need to increase your ISO,” he adds.

Julio also suggests I use back button focus, allowing me to focus faster and free up my shutter button so it just takes photos.

“The idea of street photography is to work quickly and unseen, like a ghost,” he explains. As a result, I’m told to dress in clothing that won’t draw too much attention when we’re out shooting. “Photography vests are officially banned,” he declares. To help me blend in I wear a dull shirt and plain shorts, but I’m still resigned to the fact I’ll probably stand out as a complete tourist.

Julio’s camera gear is basic – a Canon 40D from 2007 with a 28mm prime lens. In his eyes, modern gear isn’t necessary and he baulks when I suggest bringing along a 50mm prime to accompany my 35mm. “There will be no changing lenses. You will take one lens. If you are busy messing with your camera settings or gear you will miss the photo.” As Julio explains, the right moment is magic. “It can appear and disappear in milliseconds – don't lose it forever!”

When he’s not looking, I discreetly change my drive settings to single shot to match his – but my spare lens stays safely at home.

It’s simple and direct advice like this that has helped Julio become an in-demand photo tutor and lecturer, as well as probably the only person in Cuba doing street photography. Originally working as an English speaking fixer for visiting photographers and filmmakers, Julio became friends with Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey who graciously took him under his wing. “He taught me the basics of composition by drawing the rule of thirds on a napkin,” remembers Julio. “He was a great mentor for me.” Julio was also lucky enough to work closely with British photographer Keith Cardwell, who has visited Cuba many times.

Gifted an old film camera, Julio began taking photos but quickly realised there were no studios in Trinidad where he could develop his slide film. So, like many Cubans, he had to improvise. “I’d send my films to friends in the US – they would be the first ones who’d see the shots. I felt great pressure – if I’m going to go to the trouble of sending my photos to America, and then expect my friends to develop and send them back, they needed to be good. It forced me to work harder and get better.”

With a laugh, Julio explains he also saw something that few other people in Cuba had considered – the potential for photographs to connect with an overseas audience hungry for nostalgic images from a place so recognisable. “I got great money for the first photos I sold to National Geographic Travel magazine,” he says to me, grinning. “It helped pay for this lens.”

On the streets

My initial camera set-up over, we’re now out on the street and already surrounded by countless photo opportunities.

“With street photography, you must take control of your camera,” Julio explains as we narrowly avoid a wheezing old car. “In landscape photography things don’t move – out on the street if you let the camera dictate, you’ll miss the shot.” Time is the most important thing here and using it quickly becomes Julio’s mantra. As if proving his point, I spot a photo subject moving past a beautiful pastel wall but by the time I lift my camera and try to frame her, the old lady has moved on.

Meanwhile, Julio’s ahead of me and getting set to show me how he works. “See this girl walking down the street towards us in a school uniform?” he points. “She’s going to school and I want to show her with a sense of the environment she’s living in.” Moving slightly round a corner, Julio carefully avoids capturing two modern cars in his frame, but ensures he includes the old buildings and walls behind her that characterise Trinidad. She’s getting closer. “I want to frame her against these walls here and wait for her to be in full stride, so there’s a sense of movement.” As she steps out onto the road in front of him, Julio lifts the camera to his right eye, takes a shot and is done. She doesn’t even notice.

He looks at me and grins. “You don’t have to ask for permission if the subject doesn’t know they’re a subject.”

John Wayne

Julio’s style is about capturing candid moments like this quickly. “I call it a John Wayne photo style, shooting from the hip, fast with anticipation,” he explains. To illustrate, we approach two chatting cowboys on their horses, but they spot our cameras and self-consciously sit upright, their conversation grinding to a halt. We wait. They soon relax and continue their conversation. In a flash, Julio frames his shot and takes a photo.

With Julio’s basic camera gear, he’s limited by how much he can crop so prefers to have his frame ready in his mind before he shoots. Composition really is key and he lives by the rule of thirds. “A photo is two dimensional, but you can add a third dimension by suggesting depth – just look at this for example.” He shows me how he included just a tiny part of the road behind the cowboys, in doing so bringing the image to life.

By shooting in shutter priority and constantly keeping an eye on his shutter speed on his top panel as the light changes, he always knows his images will be exposed correctly. He’s also a strong proponent of using the viewfinder, not the rear LCD. “With the camera held up to your right eye your left is free to see what is changing in the scene in front of you,” he explains. “You can’t do that when you have both eyes on your rear screen.”

His other tips are just as simple. When holding the camera, keep your left arm ‘like a tripod’ with the elbow near the body. “That way, it’s steady and solid and the camera won’t shake,” he says.

As we move on, he encourages me to get close to my subject. Very close. It becomes another mantra.

“One of the joys of teaching photography for me is getting people to ‘break the line,’ he says, as we walk out of the tourist part of town and into a grittier area seemingly more popular with horses than cars. “Often people are scared to get close, but when they do, it’s wonderful to see.”

It’s also why Julio favours the simplicity of prime lenses. “If you’re shooting like a sniper far away with a big telephoto lens, your life isn’t on the line and your photos will show it,” he explains. “I prefer to use my feet.”

In practice

With Julio’s advice ringing in my ears, I spot a young musician leaning against a wall at a juice stand. I get close, and then closer still, carefully ensuring I don’t exclude too much of the environment around him, before taking my single shot – it turns out to be one of my favourites from my trip.

With inspiration seemingly everywhere, it’s no surprise that Julio rarely takes photos outside of Trinidad. In his eyes, it doesn’t matter if you’re not a local either – what’s more important is having the confidence to take photos and a clear understanding of what you want. By the time I leave, I’m already looking at the city in a different light, but his tips can be used anywhere – you don't have to be in a photographer's paradise.

Almost as often as you hear the expression No es fácil in Cuba, you hear the word 'change'. US President Barack Obama recently visited, and just after I left Cuba, rock band the Rolling Stones took to the stage in Havana for the first time ever. Mick Jagger told the 500,000 strong audience that ‘the times are changing’.

When the band first began touring in 1964, Cubans were forced to exchange their music on pirated records and many were being arrested for 're-education'. Today, entrepreneurs like Julio are just the kind of change that the band was talking about. Cubans are reinventing themselves to adapt in a changing world. It’s still not easy, but given time, it will be.