Profile: The Light Collective

It was once said that the secret to a good photograph is knowing where to stand, but Ansel Adams probably wasn't thinking about aerial photography when he said that famous line many moons ago. Anyone who has tried taking photos from an aircraft will know that being in a moving and vibrating box thousands of feet in the air while trying to take images doesn't lend itself very well to being up on your feet.

But it's not like sitting still is in the vocabulary for photography quintet The Light Collective either – they've just launched their first project, comprising a book, video and large-scale exhibition all inside a year, and there's more to come soon.

The collective

In the vein of collectives like Oculi, Pool and even Magnum Photos, The Light Collective is a group of five landscape and fine art photographers from around Australia who have pooled resources and shared their not insignificant expertise together. In practice this means working from a different perspective than usual – and one they have chosen to do from up above for their first project.

“At the beginning we were all aware of each other through the photographic community, and some of us were working together on workshops as well,” says collective member Luke Austin, a fine art and landscape photographer from Perth. “But it was Ignacio Palacios who first approached me and the others about forming a collective in 2014,” he explains. The collective now comprises Austin and Palacios, as well as Melbourne's Ricardo Da Cunha, Tasmania's Paul Hoelen and Sydney's Adam Williams.

One of the great benefits of working together is being exposed to new approaches and styles, and for Austin this meant an opportunity to explore aerial photography with the collective's first project, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre – Interpretations from the air, something relatively new to him. “I certainly don't think of myself as an aerial photographer and am much more comfortable doing traditional landscapes,” he admits, “So to work with others who are so experienced in the air is priceless for developing your skills.”

It can be easy to think of photography as a solo pursuit as we each have our own unique vision and style with image making. “Photography can be a selfish thing,” agrees Austin. “Like most people the reason why I do it is to get away on my own, but to get together and collaborate as a group means you can really push each other outside your comfort zone,” he says.

This ability to bounce ideas around is handy to avoid complacency as well, something that affects all photographers at one time or another believes Austin. “Sometimes you may think something won't work or it's not worth endeavouring to do something, but when you have a group of five people you push each other along. There's always someone who is able to pick up the slack too. You just get more done as a group.”

The project

The collective knew they wanted to focus on an area unique to the Australian landscape for their first project. “It was also important to us that the location we settled on hadn't been done to death and if possible reflected our interests in protecting the environment,” explains Austin. Envisioned as the first part of a wider long-term Australia-wide project that will seek to interpret from a photography perspective three distinct bands of colour in the Australian landscape - red, green and blue, Ricardo Da Cunha suggested as a starting point Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre for red, the iconic vast and dry expanse of salt in the South Australian Outback some 700km north of Adelaide.

Situated in a basin so large it crosses the borders of three states, the lake is typically dry but fills every eight years or so. On cloudless days the seemingly featureless landscape is known to almost merge with the horizon, making it difficult to distinguish between land and sky – an illusory effect that has caused several aircraft crashes, while also making it a challenge to photograph.

With the location locked in, the collective started thinking about how best to photograph the lake – from in the water, on the surface, or from above. “We eventually decided from the air was the best choice because of all the incredible textures and patterns, shapes and colours,” explains Austin. Ironically, Da Cunha was the only member of the collective who couldn't make it when they set out on the trip from Adelaide to photograph in early May 2016.

With only limited space on-board for shooting once in the aircraft, the guys started by diplomatically drawing straws to decide who would get the prime photography spots next to the open door and in the front seat. This soon went out the window and by the end they were having running races to the plane – there's nothing quite like competition amongst friends. But they needn't have worried: by the time they called it quits a week later, each had spent about seven hours in the air.

With no sense beforehand of what they might see, Austin says he was stunned to discover just how visually striking the lake was from above. The dreamtime story of the Arabana people, the traditional custodians of the land, tells of how the lake was formed from the skin of a Kangaroo where it was laid down in place after being hunted and killed. In his introduction to the Kati Thanda book Paul Hoelen describes how witnessing the worn, dried and wrinkled folds unveiling themselves in the terrain made this seem all the more real.

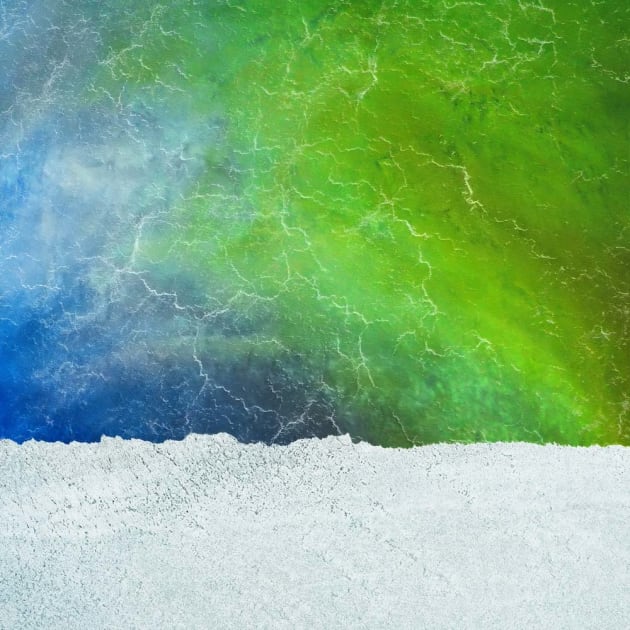

Recent flooding leading to the biggest influx of water in the area since 2011 had created an explosion of colour as water cascaded down the vast basin. Beautiful rivers and algal blooms created amazing contrasts that could only truly be appreciated from a birds eye view. Each of the photographers came away with their own interpretations.

“The parts of the lake where there was interaction between the water and the land looked the most dramatic to me,” explains Austin, remembering the scene. “But I was also drawn to areas where there was a thin layer of water on the salty ground. The wind manipulating the surface in these places created amazing abstract effects, especially so as the salt deposits eroded or built up over time.”

Taming the chaos

For Austin, one of the biggest challenges of the project was trying to compose images that worked in a graphical sense. “A lot of the scenes are initially quite chaotic, and it's best to get composition right in camera rather than risk losing valuable pixels cropping later on,” he explains. This required smart shooting to exclude anything extraneous and a keen eye to really focus on contrast and defined points of interest.

The collective quickly decided that the strongest images were those shot from a straight down perspective, and as a result of all the images that made the cut, only one or two had sky or a horizon in them. 'We wanted them to look like abstract paintings, with a real fine art feel,” says Austin.

The process of selecting and editing individual images was a long and difficult one, before the photographers got together to present their best work and decide which of the thousands of shots would make the cut for the hardback book curated by designer Douwe Dijkstra.

The result of the two year long project is a series of remarkable beauty and consistency. Along with the 128 page book and behind the scenes video of the entire shoot, the collective also made a group selection for a Kati Thanda exhibition which launched in Sydney in December and has spent much of 2016 and 2017 touring Australia.

The Gear

Although modern digital cameras mean aerial photography is more accessible than ever, a camera with high ISO capabilities and image stabilisation is still probably the single most important factor for success with aerials as shutter speeds have to be fast to overcome the constant movement and vibration from the aircraft. For a project like Kati Thanda, ensuring the resulting images would be big enough for large prints was also a key consideration.

Austin's choice was a pair of full-frame Nikon bodies - a D800E and D810, along with a 'slew of lenses' he says, although he often found himself reaching for his 85mm 1.4 lens first. “I liked using a longer focal length as it helped isolate some of the patterns below,” he explains. The others took a similar approach, with Ignacio Palacios choosing a full-frame Pentax 645Z medium format body, Adam Williams the Nikon D800E and Paul Hoelen choosing to use a Canon 5DS.

Up in the air, for Austin it was a matter of keeping an eye on shutter speeds, with 1/1600s to 1/2000s the ideal. Using auto ISO capped at a minimum of 100 and a maximum of 800 helped ensure images were relatively noise free.

From an image-making perspective, Austin says he also found that stitching gave good results - taking four images in the air to be blended later for maximum resolution.

The future

For The Light Collective, Kati Thanda is definitely just the beginning. The next part of the project will involve exploring the other colours that make up the landscape of Australia, with the Great Barrier Reef for blue and the Tarkine Wilderness Area in Tasmania for green being considered as options.

“What is most important to us is showing mother nature in all her beauty while still putting our own unique stamp on it,” says Austin. “I also hope people can look at what we've done by collaborating together and see how great it is for developing their own photography.” ❂