Profile: Warren Clarke

Early 2018 saw the untimely passing of one of Australia’s most revered and well-respected photographers. With a career that spanned several decades across most continents, he touched the hearts and minds of photographers around the world. This is the story of a character, a traveller, and a photographer, but most of all a friend, from some of those closest to Warren Clarke.

On January 27th, 2018 a Facebook post from the Oculi collective shook the Australian photography community. “A heavy heart has fallen on many,” said the post, “with the news of the passing of our dear friend Warren Clarke.”

Accompanying the text; a photo of a Mursi tribe member in the Omo Valley of Ethiopia, a view from a taxi window of the holy city of Qom, Iran, and an Afghan amputee considering his new prosthesis in a mirror in Kabul—a visual whirlwind tour of the career of one of Australia’s most celebrated photojournalists and perhaps its most intrepid.

But while Warren Clarke’s career was certainly defined by his seemingly insatiable thirst for travel, his investment in the people he met along the way was far from fleeting. Following Oculi and others’ tributes to Clarke on social media, an unending stream of eulogies quickly poured in.

Some of Australia’s most well-known young photographers recalled Clarke’s guidance and kindness that their careers now rested upon, while a spectrum of names and nationalities became testament to Clarke’s legacy and memory that was still very much in the minds of his subjects across various continents.

Oculi’s praise for Clarke went on to detail his unmatched role in the formation of the collective—a group that has since become a mainstay of documentary in Australia and emblematic of Clarke’s legacy in thoughtful, considered photography.

From his humble beginnings in an outback town, Clarke would also go on to photograph the effect of landmines throughout the world and his on-going in-depth focus on India would become his magnum opus. And it was this commitment to photojournalism that saw his work appear in publications and across wire agencies around the world.

“Waz, you recently said to one of your many friends, that you felt like you have lived three lives”, continued Oculi’s tribute. “Indeed mate, and each one of them were full.”

The early days

Growing up in a small country town in rural Queensland, Clarke’s father was a hard-working builder and, although he rarely spoke of it to his peers or colleagues, Clarke himself was an accomplished horseman, winning an array of contests at various levels.

Across both his professional and personal lives, it would seem that this unassuming background imbued Clarke with an immense sense of humbleness and despite what colleague and dear friend Michael Amendolia calls a “ratbag” side to him, Clarke was known for his modesty.

Throughout even his early career, this trait—a large reason behind his almost unanimous moniker among his peers as a “rough diamond”—would seem almost at odds to the very impressive CV that Clarke was able to quickly garner for himself.

Discovering photography while in the UK as a young man, Clarke cut his teeth as a photojournalist after finding a job shooting for an East London newspaper before moving back to Australia to take on freelance press work at News Corp.

It was around this time that Clarke began to work shoulder to shoulder with some of the country’s best shooters, from Amendolia to Russell Shakespeare, Trent Parke, Stephen Dupont and Glenn Hunt. The group—a rag-tag mix of freelancers and staffers from News Corp and Fairfax alike would meet periodically for “slide nights” that would eventually go on to become the infamous Reportage Festivals as orchestrated largely by Dupont.

As Amendolia recalls, it was at these slide nights that he got to know Clarke. “That fact that myself and he would get along is odd because we’re like diametrically different personalities but there is one thing that we had in common: the photography side of things,” he says.

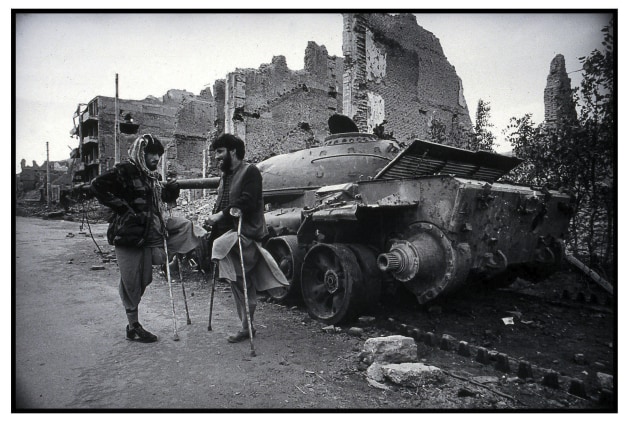

“It was sort of through that slide show crowd that we became mates. Warren would come back from Afghanistan where he had been shooting a story on landmines that he did off his own bat and show the work on those nights. He even paid his own way to Cambodia and Angola to look at this story of landmines and the rehabilitation of victims. He was the absolute consummate traveler.”

It was also around this time—roughly twenty years ago—that the Oculi photo collective formed. As the likes of Trent Parke, Dean Sewell, Jeremy Piper, Tamara Voninski and Nick Moir negotiated the thriving but also untamed photojournalism scene in Australia at the time, the need for a group with a loud cohesive voice gave rise to the now infamous aggregate of documentarians. And as Jeremy Piper recalls, Clarke was at the front and centre of the effort.

“He was there for all the early days, the initial set-up and the meetings. He was a core founding member, he had all these ideas and direction and a strong stance on things but he, like the rest of us, was full of ideas and wanted an outlet for pictures,” says Piper.

“He really helped to form our collective belief and what directed the group—even to this day. You learn from people like that and you need those people in your life to direct you in those ways. Warren was someone that directed both my life and my work. But you don’t really see that until someone goes, do you?”

Guiding light

Piper’s testament to Clarke’s impact on not only Oculi but also generations of Australian photographers is surely most recognised in his unwavering ability to tell stories with incredible sincerity.

“I think the selection criteria for the group at that stage was ‘who has been shooting photographs that mean something’ and his work stood out among all the rest of us in that way,” says Piper. At a time when unrest in the Middle East was coming to its peak and a suite of Australian photojournalists were uprooting themselves to cover the conflict while embedded with troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, Clarke’s ability to transcend more reactive modes of reportage was affirmed by a chance encounter with James Nachtwey, who shared Clarke’s belief that the story of war was felt most far behind the front lines.

“He was really concerned about the effects of war on people. In those situations, you can be there on the front line but you can also look at the on-going issues and implications,” says Piper. “I think Warren’s approach was to look at the implications of the decision makers and the broader effects of war. He really had a connection with those guys; with the victims. And at that stage, much of those stories weren’t really being told.”

Although Clarke will be often remembered as a photographer, many of his closest friends are also quick to point out that his kindness, his interest in people and his love of life were not centred around his camera.

“Warren often travelled for photography but it was also just so much about the experience for him. He was the sort of guy that could just throw you over his shoulder and walk 5km if he had to,” says Amendolia, recalling a particular anecdote that illustrated Clarke’s flare for discovery on the world’s highest mountain.

“It was no drama for him to go to Everest base camp by himself with no guide in winter. He actually did that.

He got caught in a bit of a blizzard and couldn’t find his way back to the village he was staying in. Luckily, he came across some locals that pointed him in the right direction. That’s the way he travelled.” Back home, Clarke was also known among his friends as a great cook, a facilitator of youth boxing in Sydney and to the delight of a memory recalled by friend and fellow photographer Russell Shakespeare, an espresso connoisseur.

“On all of his travels, he carried around a portable espresso maker—like, one of those pump things so he could always have his special coffee. When I arrived in Varanasi, the first thing he said was, ‘Mate, do you want a coffee?’ and I was like ‘What!!??’.

He was one of those people that came across a little rough at times and he would say what he was thinking but at the end of the day if you wanted someone who was going to stand by you through thick and thin it would be Warren Clarke.”

Indian odyssey

Shakespeare’s memory of Clarke and his espresso maker in Varanasi is emblematic of the last trip the two spent together in India. While both photographers have focused extensively on the sub-continent, in the last three years of his life, India became the subject of Clarke’s most extensive work, spending months at a time travelling the area with the goal of seeing and photographing the entire country.

From 2015 to 2017, Clarke photographed tens of thousands of images: street scenes, portraiture, daily life, landscapes and ritual, all photographed in black and white, comprising an enormous archive of imagery that has since formed the basis of a commemorative book edit by Shakespeare and Amendolia.

As the pair explain, the mammoth task of sifting through Clarke’s extensive archive was largely informed by his love of experience and of travel itself rather than an obsession with the photographic results of his endeavours. “That’s why he didn’t have so much of his work finished, edited or at least partially edited as he went along with this India project,” says Amendolia.

“Warren was living life and having the experience of travel. The photos were there as well but he was a real traveller. Rather than coming back to his hotel every night and editing, he would be out and about socialising with the locals or whoever he was travelling with.”

During his three years photographing, Clarke’s vision of India and his skill in photographic inquiry were largely informed by the greats of photography he looked up to but were also relayed in his philanthropic efforts. Clarke had a library full of books and was an astute reader of classic publications from the names of Gilles Peress, Alex Webb and Steve McCurry et al—all of whom undoubtedly informed his ability for dynamic yet thoughtful compositions.

However honed his skills, Clarke’s eagerness to share his insights and knowledge were made clear in his very last days in Kashmir where he held informal workshops with local photographers.

“A lot of them wrote to us and said they couldn’t believe that he had died because only just a couple of months earlier he had been doing tutorials to their photography groups,” says Amendolia.

“He was sharing his insights with the local Kashmiri photographers and that was only months before he was told he had a brain tumour.”

Final days

It was around this time of Clarke’s latter work in India that he was having trouble sleeping. Returning to his family home in Brisbane in mid November of 2017, it was roughly a week later when Clarke collapsed on the floor of his parents’ house and was given about 18 months to live.

With the news of a year-and-a-half left of life, Shakespeare and Amendolia set to helping Clarke with the gargantuan task of editing his Indian odyssey. “I’ve been doing Momento books for years now. Last time Warren came to my place he had a look at them and that’s what he wanted to do,” says Shakespeare.

“But sadly, he had only done his first edits and we were thinking that he had a bit more time but it just wasn’t to be.” On the Monday before he died, Shakespeare and other close friends sat for dinner at the Clarke family home. “He was eating and drinking for Australia, like no problems. And then the next morning we went for an 8km walk,” recalls Shakespeare. “In the end, he only had less than three months. We all didn’t expect that.”

While the constant stream of messages from around the world serve as testament to the untimely and unforeseen nature of Clarke’s passing, more importantly they prove the long and impactful legacy that Warren Clarke has left for his family, his friends and his children Jack and Isabella.

While those who never met him will mostly remember his photographs—the images from far-flung corners of the globe to which most of us will never travel and of the people fortunate enough to have encountered Clarke along the way—those close to him will remember Warren Clarke as the “rough diamond” that he was affectionately referred to by many.

“He just touched so many people in so many regions of the world—it is such a testament to a bloke, you know,” says Piper. “But that’s the most disappointing part: that he had so much more to give. You could see it and you could see it in his pictures.”

“Your eyes told us much about other lives and also just about as much as they told about you,” a tribute from Oculi goes on to say. “A good man who can hold his head up high as you take the next journey. Not sure what the light will be like though… you’ll be right.”

Vale, Warren Clarke. ❂