Steve McCurry: The interview

Steve McCurry’s career in photography first began with a job on a local paper in the unusually named town of King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, USA. Some photographers can spend a lifetime on local news and develop a satisfying career, but McCurry always had other plans.

He wanted to see the world he says, “to wander and explore at my own pace”, and he wanted to do it in far-flung locations, where the cultures and environments were vastly older than that of his home country. He had studied filmmaking at university, but discovered that it was a collaborative effort, usually involving a large number of people.

Stills photography, however, was a craft where you could work outdoors, and more importantly to the young photographer, you could simply “start work”. “I wanted to follow my instincts and intuition,” he says. “I wanted to see the world and visit cultures all over the planet.”

So he did.

Working in a War Zone

McCurry’s first stop was the Indian sub-continent, where he spent two years producing photojournalistic images.

“I researched story ideas before I left and I hit the ground running," he says. McCurry says the environment in that part of the world was intense. “There’s the heat and the crush of humanity, but it’s a fascinating place.”

After 18 months he found himself in Pakistan, where he came across Afghan refugees. The story they told him piqued his interest, and within a short space of time he was following them back across the border into Afghanistan to photograph a civil war. It was something he had always wanted to do. Then the Russians invaded in late 1979, and McCurry found himself as the only working photographer on hand to shoot the invasion.

Later, he took the photos to National Geographic and Time magazine. They immediately wanted his images.

“It was a turning point for me,” he says. He would return to Afghanistan and stay for two months, and he has been back many times since.

The Afghan girl

In 1984 during another visit to the sub-continent, at a camp in Peshawar, Pakistan, McCurry shot an image which would define his career, and which is one of the best known photojournalistic images in the world. It was simply called “Afghan Girl” and it was a portrait of a young girl with stunningly intense, green eyes.

Wherever he is, McCurry loves to photograph portraits of local people, and he has taken many equally powerful portraits both before and after he shot this one. But it somehow captured the imagination of people around the world, in a sense summing up both the intensity and despair of conflict in Pakistan.

The image is iconic, and resonated so strongly with people that almost two decades later, in 2002, McCurry returned to the region to find the girl, Sharbat Gula, who was now a middle-aged woman. He was part of a documentary crew who filmed the search, offered compensation which Gula and her husband used for the education of their children, as well as once again taking her portrait.

He says now, “She was a striking little girl with an amazing look. I knew when I saw her it was going to be a powerful portrait. But her parents had been killed and life was difficult for her. When I began to search for her again I was told she had died in childbirth or been killed, but 17 years later we found her. It’s a very conservative place there, but we were happy we found her and [I was] relieved she was alive. I think she was happy she came to represent Afghanistan.”

McCurry says he hasn’t returned to Afghanistan for about two and half years. “There are other things I want to shoot, but I think the whole occupation over there is a mistake. After September 11, I think it was important, but there has been an enormous waste of human life, time and money since then. They’ve proven they want to go another way. Let’s see what happens.”

Changing world

McCurry says his time in Afghanistan made his reputation and opened the door for many other assignments. From Afghanistan, he shot two assignments in Pakistan for National Geographic, and then went on to work around the world. He is in an ideal position to note how working as a photojournalist has changed with time.

National Geographic was renowned for the vast amount of resources it poured into its stories, but McCurry says, “Getting a lot of resources and time doesn’t necessarily guarantee a result.” McCurry says National Geographic assignments today are much more focused, and extend over shorter time periods.

“For instance, you wouldn’t go to Brazil with the idea of shooting the whole country. You’d take less time and do a region, or maybe Rio.” He says that decades ago, an assigned shooter might have unlimited film stock for the job, and local assistants. “But you used what was needed, and I wasn’t spending much anyway.”

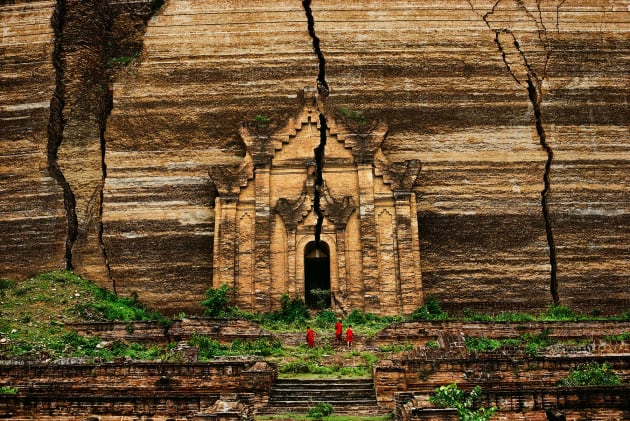

McCurry has a great affinity for and fascination with the regions he has become most identified by – the Indian sub-continent, China, and the Middle East. “They are ancient cultures,” he says, “In other parts of the world the colonial period overshadows ancient cultures,but in these regions they already had pretty advanced civilisations and religions. To me, that offers more depth than other parts of the world, although Africa is endlessly fascinating.”

McCurry says that because stories for National Geographic are now much more focused, “you don’t need to spend six months or a year photographing everything that moves. You’re shooting stories, not novels. It’s better journalism and it needs more thought.”

Diversifying

McCurry says that he now does a much wider range of jobs than he did 20 years ago. “I work on books, exhibitions, and fine-art images. I have so much archival material, and I do other projects. This is the world I live in.”

He acknowledges the photographic world has changed significantly. “There’s probably more photographers than the industry can sustain. But now you can literally build your own website. In a way you can say the same thing about writing – everyone can write, but the ones who have something to say rise to the surface. Virtually nobody wants to use the discipline required to write a book.”

He continues, “Every man, woman, and child has a camera, but that doesn’t mean they will make one meaningful picture. Around 99 percent of the images taken now are personal pictures. It’s consumed an enormous amount of my life to really develop a body of work. If you’re driven or compelled, you’ll do it, because it gives meaning.”

Photojournalism has changed significantly in recent years, as has the world of magazine publishing, and that has all impacted McCurry’s work. “In some ways the old opportunities are not there. The status quo has changed and there are new ways to work. It’s still evolving,” he says. “But buying a camera and calling yourself a photographer doesn’t cut it.” He says of the dramatic change for many professional stills photographers where they’re now often being asked to shoot video as well, “That’s the world we live in.”

The techniques

Technically, McCurry's approach has been honed by years of shooting unforgiving transparency film, where exposures had to be almost exactly right or an image was written off. The so-called “latitude” of slide film was extremely narrow, so that highlights could be easily blown out and the image ruined. Only to a marginally greater degree would slides accommodate under-exposure. So McCurry learned to recognise when the light was “right” for shooting. He also learned to work with the soft lighting often present in the sub-continent, where low-light, low-contrast images became a staple of his style.

Interestingly, despite his preference for low light, his portraits almost always incorporate catchlights in the subject’s eyes, a vital spark which can really lift these types of images.

In 2003 McCurry moved to digital, but he didn’t change this basic approach. He often works in low light, but shooting digitally allowed him far more scope to use those conditions. “I prefer low-contrast light, and I tend to get up early,” he says, “But not for the light.”

McCurry is reluctant to discuss any specific techniques about his craft. But he is happy to discuss a philosophy. “Make a point of practicing,” he says. “Perseverance, fortitude, and discipline. There are no shortcuts, and no silver bullet.

The unfortunate thing in life is that there is a lot of work involved, and often it’s tedious work. Some people buy a camera and wait around to get assignments.

It’s wonderful they’re that naive. It’s like telling me you’ve got a first-aid kit so now you’re a brain surgeon. You have to find your own way.”

He also says he has, “virtually no interest in equipment – period.” He says, “It’s not what motivates me. I don’t want to talk about gear. Any camera on sale today will give you wonderful results. It’s how you do what you do, and whether you enjoy your photography. Manufacturers want to sell their cameras, and their ads are the same now as they were 30 or 40 years ago.”

But he says, “The status quo is changing. If you only want to look back and don’t try to be creative, it’s bleak. But with ambition, it’s bright. Moaning is a waste of time.”

"We’re all fascinated with each other," he says. "We all basically do the same things in life – get up, go to work – but in different places we do it in different ways. That kind of life on planet earth is endlessly fascinating.”

Interview first published in Australian Photography, March 2013.